This situation was amusingly summed up by another famous researcher. If that sounds to you more like the nonsense babbling of a parrot, or what your dog might say to you if he saw that you had an orange, and much less like the thoughts of a child, you can see the problem. Nim once formed a sixteen-word sentence: give orange me give eat orange me eat orange give me eat orange give me you. But they rapidly develop the ability to form longer sentences, conveying meaningful thoughts, asking questions, and expressing new ideas. Human children begin with short sentences. The general pattern was: Nim or me followed by eat, play, tickle, banana, grape, or the like. Terrace noted that nearly all Nim’s sentences were two or three words long extended sentences were very rare. Usually these sentences were very short, and in no sense grammatical. Most of that footage demonstrated the apes producing word salads that contained signs for food or affection they desired. When Terrace did this, he found that interesting sentences began to look like drops in the ocean. Is water bird the intellectual combination of two concepts to indicate a waterfowl? Or is it just rote repetition that a lake and a bird are nearby, combined with generous and wishful human interpretation? Studies in the field generally focused on picking unusual instances out of thousands of hours footage, rather than systematically studying whether apes expressed meaningful ideas. What’s more, the meaning of the signs was very easy to over-interpret. But, this makes the interesting sign combinations look more like generous interpretations of anecdotes that were cherry-picked, or fed to the ape by human handlers, and not a conscious thinking pattern. What about the heart-warming stories of human-ape understanding? Human handlers interacted with the apes for thousands of hours, and occasionally the human interpretation of a string of signs would stand out as interesting. The animal was essentially mimicking the human’s behavior. He noticed that the researchers prompted the apes by displaying signs to them, in English grammatical order, before recording the same signs repeated back by the ape. Specific frames and traced images from them are demonstrated in the paper.

Terrace carefully reviewed video footage of human-ape interactions. This paper became the seminal work in the field - and likely the source of its complete undoing.

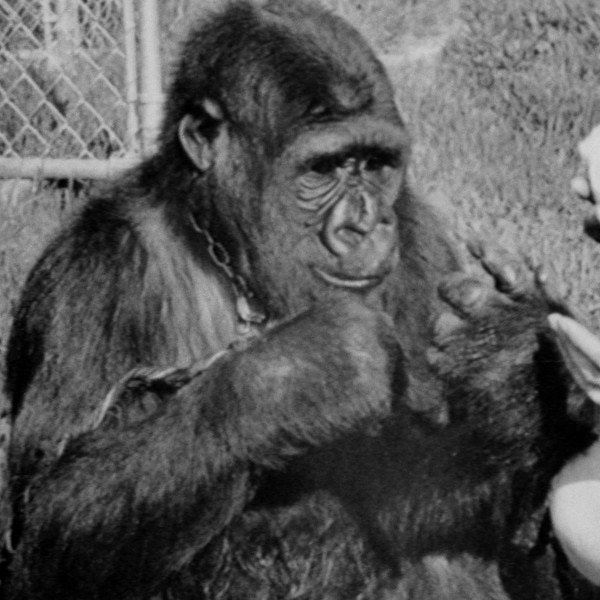

At the end of the study, he wrote a 1979 article in the prestigious journal Science. Terrace rode the results of Project Nim to academic stardom in the 1970s. One of Nim’s handlers reported that the animal requested the substance. She also breast fed(!) the chimp and supposedly taught him to smoke weed(!!). His foster mother, Terrace’s student Stephanie LaFarge, taught him ASL. Nim was raised like a human baby in a Manhattan apartment. Nim Chimpsky - the name is a pun referring to the prominent linguist Noam Chomsky, then known for his groundbreaking research on linguistics - was his personal research study subject. That researcher is Herbert Terrace, a professor of psychology at Columbia University. Among these experiments, the story of one researcher and his chimpanzee stands out. The animals appear to form thoughts and express them in one of our languages to meaningfully convey their ideas to us. The Koko project released a video of the namesake gorilla delivering a message about climate change. The bonobo Kanzi learned to point to various symbols that represented about 350 words.

When the chimp’s handler disclosed that her baby had died, Washoe reportedly signed back cry. Stories of ape sign language can feel shockingly human.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)